Page status: CompleteVersion: 1.1| January 06, 2018

Contents

Iterative Publishing

Is this the Final Version?

Author: Chris Jennings

Note: An edited version of this article appears in the journal Logos 1. The contents of this paper was given in a presentation at the By The Book Conference in 2017, Florence.

eBook Version available here (click image for ePub download)

Abstract

Why do publishing students (or indeed publishers), save their files with such names as finalversion1?

Of course, we all know that it can’t be the final version - we all just hoped that it would be!

Books like other created artefacts go through a number of iterations before being ready for public display. The question is, can we observe and record what those changes are and when they happened, and by whom?

In this article we look at the way that the reader of the book will know what version they are reading and the author / editor will know what version they are editing. We look at this in relation to print, digital and author or editor workflows.

Introduction

We should start by announcing a couple of quotes.

Semantic Versioning

The first is from the organisation known as semver - short for Semantic Versioning. The Semantic Versioning2 specification is authored by Tom Preston-Werner, inventor of Gravatars and co-founder of GitHub. Here is the quote from Jurgen Van de Moere3, who explains semantic versioning better than I can:

In essence a semantic version looks like this: Major.Minor.Patch So v1.3.8 has a major component with a value of 1, a minor component with a value of 3 and a patch component with a value of 1.

Apple’s Rules for eBook Versions

Apple are very strict when you want to update an eBook on the iBookstore. Here are the rules from the iBooks Asset Guide4

In general, the first number of the version number represents a major revision; the second number would be used for a revision containing several changes/new information; the third number would be used to indicate minor changes, such as fixing a typo or formatting issues. For example, if the first version of the book was 1.0, a subsequent minor revision could be 1.0.1; a more substantial revision could be 1.1; a total rewrite could be 2.0.

These 2 quotes set the scene for what is to follow.

What do we know about versioning in print and digital publishing and how might we borrow from practices in software development workflows?

Part 1: Public Facing Versions

Definition of Terms

Edition is used together with a date (just the year), to indicate the version of the book. So, if you are reading a later edition of the book then it might say so with the date; thus:

First published in Great Britain 2012 This edition published in 2017

Some changes were made to the book between 2012 and 2017. So, edition is equivalent to version in meaning, although only publicly available, not within the editorial workflow. We have only seen the term version used in one place, The Elements of Typographic Style, Robert Bringhurst, 2012.

Revise may be used to indicate a stage in the editorial process as in revise 1, revise 2. Some publishers may also use revised edition on the imprint page as a way to indicate improvement.

Impression is a term used to indicate a new printing. The term is rarely used on the imprint page, although you will see in the illustration here that OUP have recently replaced the impression sequence numbers with the term Impression 4.

A Reprint may be the same book but with some changes, although unless you see something like “with a new preface by …”, then you may not know. A reprint could be same content but reset with new type. It is different from a facsimile which is an exact copy (page-by-page), often used to re-publish legacy content that can only be taken from printed pages.

Errata are corrections to a book when it has already been printed. The corrected errors are printed on a slip of paper and then glued into the front matter of the book before distribution. This happens very rarely, since this give a negative impression of the quality of the book. Since many books now have a companion web site, these corrections are often to found listed there.

In Print

There are a number of conventions that have been used over the years, and some style guides do attempt to establish some kind of standard, if only for their own processes.

In The Chicago Manual of Style5 we do find:

The publishing history of a book, which usually follows the copyright notice, begins with the date (year) of original publication, followed by the number and date of any new edition. In books with a long publishing history, it is acceptable to present only the original edition and the latest edition in the publishing history.

and also from The Chicago Manual of Style with reference to impression numbers:

Impression lines work to the advantage of readers and publishers both—a new impression not only reflects the sales record of a book but also signals that corrections may have been made.

When it comes to marketing advantage, there must always be a benefit it proclaiming New Edition, just as there is when we see a food package on the supermarket shelf that announces with a flourish: new improved Recipe.

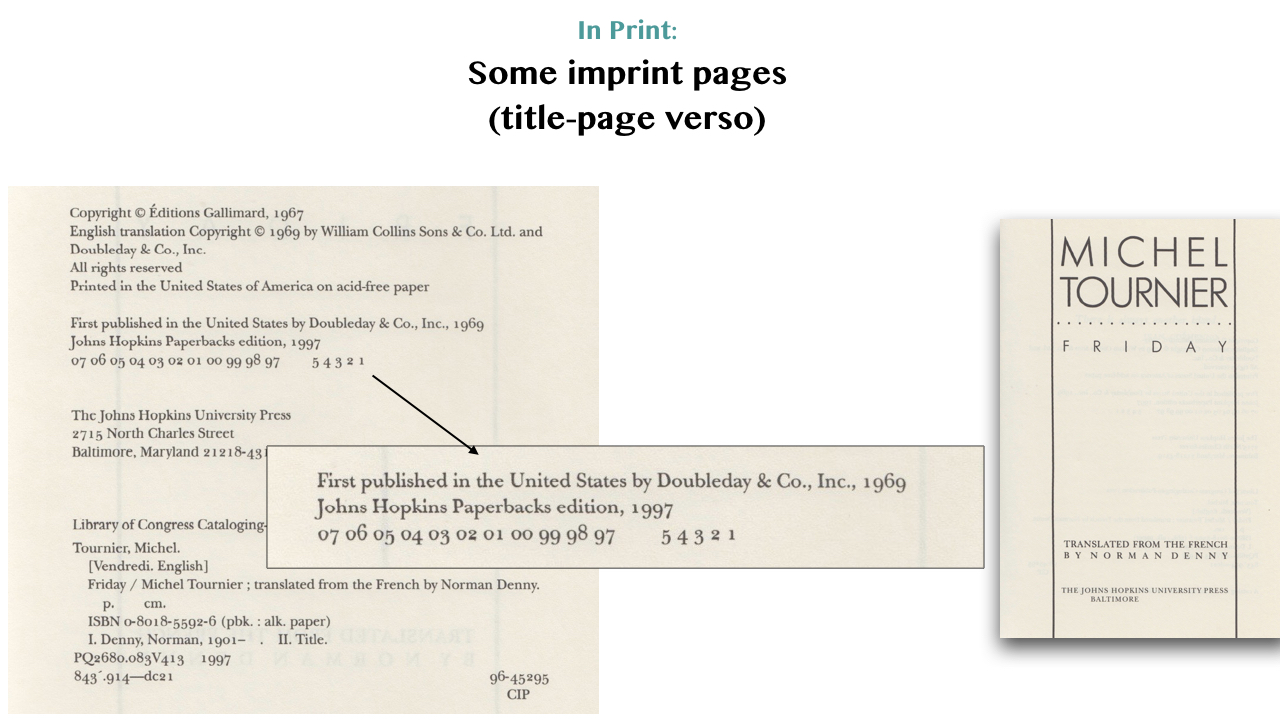

Imprint pages (title page verso)

When we explore imprint pages in the books on our shelves we find some interesting publishing messages.

Book collectors, of course, prefer to own first editions, so in their collections there will be limited information; just the first publication date. On the other hand, popular titles (see here ‘Treasure Island’), will have many reprints and new editions up to the date of the edition you have. Many reprints could be an indication of the popularity of the title, although imprint pages do not tell us how many were printed. One could argue that many reprints show that the publisher was not confident enough for a longer print run in the first place.

As an alternative to taking a lot of space on the page, you see here from the 1949 edition of Winnie the Pooh, that it had been reprinted 38 times before this “Thirty-ninth edition”. This seems to be a misinterpretation of the term “edition”, since a reprint is not usually regarded as a new edition.

Impression Lines are a string of numbers on the imprint page, that are incrementally erased, to show the current printing. It is interesting again, to flip over the title pages of our books to see this little cryptic message that is there for us to interpret. The publisher needs to first decide the highest number, because this suggests how many reprints might possible happen; a pessimism / optimism indicator, I suppose.

For each printing the lowest number is erased.

The convention is different in the USA; publishers there tend to include the date as well as the impression number.

You will see in the illustrations here that Oxford University Press have used impression numbers, and the popular Economics title in their Very Short Introductions series has lost all numbers 1 through 8, an indication that my copy is the 9th printing.

Oxford University Press have followed this convention until their Microeconomics title, in this same series. This now uses the less cryptic notation; my copy: Impression: 4. A rather sensible strategy, because the purchaser gets clear evidence that this is a popular title and must be good.

A more adventurous and even contemporary approach is found on a new edition of The Elements of Typographic Style, Robert Bringhurst, 2012. What has inspired the publisher to label this (even on the title page) “Version 4.0”.

By using the term Version 4.0 the publishers are making a nod towards the digital world as well as giving a positive marketing message.

Part 2: Workflow Versioning

As in the previous section, we can refer to the way authors worked in the past. You can see here a typed manuscript of The Waste Land, T.S. Eliot6, with notes and edits by himself, his wife Vivien Eliot and Ezra Pound. There is no timeline for the notes; in which order they were applied.

This is also the case when proof-readers use standard notation to markup corrections to a printed copy. The British standard (BS 5261)7 is adopted beyond the UK, but rarely provides times or staging for the corrections.

Digital Tools

Many authors and editors will use Microsoft Word and the track changes feature of that software has become the often used method to get changes, additions or corrections approved. The system provides the means to edit the text and leave comments. Individuals involved in the process are named with their comments. There is no hierarchical control; we can can each accept changes or not with no overall approval workflow. It does work up to a point, but can get very complex when changes overlay one another.

Another approach may be to annotate a PDF of the pages. Adobe’s Acrobat Reader software (there are others on the market) provides sophisticated annotation tools, as you can see here in the images. Not all software can easily edit the text within the PDF, so the proof reader is simply making suggestions for the editor to make in the original text.

Digital annotation is certainly useful but can never be as powerful as direct editing and version control of the text.

eBook Editing

I add this as a slight deviation, but in my own experience, publishers of eBooks really need a good method of proof reading and annotating eBooks ready for distribution. Apple’s iBooks software, does provide annotation tools (see in this attached figure from my own book), but sharing these annotations is not currently so easy. The annotations are nicely overlaid, but you can (as I write this) only email the annotations as a text; detached from the pages themselves.

Editing in the the cloud

Cloud services such as Google Drive and DropBox do provide some version control although Google do provide apps that allow direct editing of files (Google Docs and Google Sheets), when those documents are shared for editing. Sharing documents is a nod forward to Part 5: Collaborative Editing.

Systems can be built and customised for revision control using Content Management Systems. Illustrated here are screens from an application that I have used to manage remote authors contributing to a global cookery book. Authors can input and edit their own recipes, with overall editorial control given to the chief editor, who then exports the data out as XML for use in page layout software for final ‘print-ready’ output.

Not only do these systems provide the means to see versions but also they provide multi-author access. This is something to look at later in this article.

Part 3: Publishing Incrementally

In Progress Publishing

There are some publishers who provide the tools for their authors to write and edit their own work directly. Not only is this a good strategy to manage the workflow but it can also give potential to the idea of in progress publishing. Authors and publishers can engage with the public before the work is finished.

O’Reilly Publishers have an authoring system called Atlas 8 that authors and editors have access to. At some stage in the workflow, the book available as an Early Release title. You can see in the accompanying image from the O’Reilly web site9 a title that was available with some chapters completed.

Note: Since this article was started, O’Reilly Publishers have stopped selling books from their web site. The early release eBooks are only available through their Safari Books Online subscription service.10

LeanPub is a self publishing system11. Authors use the online authoring and editing tools to create the book and then decide when to make available. You can see from the image here that this book is only 20% complete, but the author makes this much of the book available.

Authoring Incrementally

So these systems do offer the author and their editors ways to keep track of the workflow from writing to public release. The key here is that each set of staged additions and changes need to have attached some metadata that will indicate the status of the work in progress. Is the work under review, a release candidate or needs checking etc.

The authoring tools needs to give an indication of the status and there might even be alerts displayed to communicate tasks for completion.

eBooks Only

This approach to publishing can only be implemented for digital products that use an online distribution system.

eBooks published through Apple’s iBooks store can be updated with some limitations. Apple are very strict about how much an eBook can be modified and how a version must be identified. You can see in this image how a purchaser of an eBook is notified of a new version and the display of the version history that has been provided by the publisher / author.

In Print

It is really very difficult to update books in print, and from the customers’ point of view, it can represent an impact on budgets. Companion web sites can be a help here; new material or errata can be provided on a web site as well as multimedia content that relates to the book.

In the image here, we see that when Adobe (and their publishing partners, Peachpit/Pearson) release new versions of their software, they then re-version their Classroom in a Book titles. These are more than new editions; they are new books with new ISBNs.

Part 4: Editing Incrementally

Versioning for Software Code

Software engineers have used version control for a long time, so we should look at a few examples of how this works. The point is though, that these systems are wrapped-up with a working in teams model. Version Control systems for coding solve a problem, that individual writers don’t have. Having said that, it is incredibly useful for this author to be able roll-back to a previous version of a text. It should also be said that most publishing will involve more that the author. There are the copy-editors and proof readers.

We can see how the version control model works from the diagram illustrated here. When a new writing session is started, a new branch is created. Then when this version is ready a pull request is made asking effectively can I merge my version with yours, then, after a possible discussion with the team, this is agreed and the merge happens.

Images here show what this looks like with a version control system like GitHub.

Git is known as a distributed version control system (DVCS), because the edits take place remotely from the master copy. Each collaborator owns their own version (a fork) and makes a request to merge their changes to the master. Centralised version control systems keep only one copy that is checked-out by an editor, and thus, locked until they have completed their session.

Part 5: Collaborative Editing

Using a version control system means collaboration.

A distributed version control system like Git, hosted at GitHub.com, is robust and reliable. Repositories can be public or private, with access controlled by primary owners or teams.

Content can be forked and then worked on by individuals and then pulled back in to the master copy. Edits or commits are recorded and can be accepted. Every committed change represents a different version.

Essentially the file has many different states which can be retrieved. Git is a set of tools to help manage change. 12

Student Example with The Student Guide to Oxford

Git can be hosted anywhere, since the software, itself is Open Source.

For a student project where 30 students are contributing to a guide book about Oxford, we used a free system called Penflip (www.penflip.com).

You can see in the images here that the complexity of having a lot of editors is handled perfectly by this kind of system.

In terms of the actual workflow and details of the process, the text is edited with markdown 13

Once the edit process was complete (a milestone previously set) the text was converted to ICML for InDesign using Pandoc.14

Please note that Penflip is no longer operating - January 2022

Some Further Options under consideration

We can find several places where version control for text authors and editors has been developed to try to make these process easier.

Prose.io is a server based markdown tool that can be used to edit text held in a GitHub repository. While this system is effective and very easy to uses, the prime focus is editing for a web site, rather than for other platforms. 15

GitBook, as the name suggests is built to edit (also with markdown) a book under revision control within a Git repository. This goes beyond the prose.io instance described above, because the content can be exported as PDF or eBook. The management of the edits by multiple authors can be hard to resolve. 16

OmniBook is based on an open source system developed under the name of BookType. The OmniBook instance is free up to a point. The BookType software can be installed on a server but requires technical knowledge to do so.17

Editoria is a web-based open source, end-to-end, authoring, editing and workflow tool 18. As I write this article, this software is under development.

Social Reading and Annotation

It has to be mentioned that there are also some eBook reading platforms/systems that do provide an online space for sharing comments and annotations. While these systems are devised for the concept of shared reading, there is a potential to use these systems to suggest corrections to work in progress texts. Here are some examples:

Glose is a website19 that requires account authentication, where you can read existing books or upload your own.

SocialBook is a collaborative reading platform20, where readers can share annotations as they read and observe other readers annotations. As I write this, SocialBook only seems to support ePub2 and not ePub3 format eBooks.

There are also annotation tools available for web sites, and The Hypothesis Project is one such tool21. This open platform provides bookmarking for your browser, so you can annotate web pages.

hypothes.is and several other projects use an open source javascript library called Annotator which is freely available22 to add to web sites.

Version Control Systems

- Git

- GitHub

- Gitlab

- Bitbucket

- Perforce

- Plastic

- Subversion

- Mercurial

Conclusion

- Should publishers use clever version control software?

- Should publishers adopt semantic versioning?

- When publishing eBooks to the Apple ecosystem, then yes, versions need to be labelled correctly according to Apple’s rules.

- Can media and publishing students benefit from using clever version control as individuals or in teams?

- I have used collaborative editing methods for text with my students.

- We need to encourage a more robust approach to version control to avoid the confusion that comes from using arbitrary file naming, such as finalversion.

Notes

Version control for ebook publishing Pierre Thierry July 2013

https://www.w3.org/2012/12/global-publisher/statements-of-interest/34-vc.pdf

An Introduction to Version Control Using GitHub Desktop By Daniel van Strien

see Conclave at https://conclave-team.github.io/conclave-site/

http://programminghistorian.org/lessons/getting-started-with-github-desktop

-

Source: DOI: 10.1163/1878-4712-11112140) ↩

-

semver.org ↩

-

https://www.jvandemo.com/a-simple-guide-to-semantic-versioning/ ↩

-

https://help.apple.com/itc/booksassetguide/ ↩

-

http://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/C/bo8540260.html ↩

-

The Waste Land Facsimile, T.S. Eliot (Author), Valerie Eliot (Editor) - Faber and Faber 2011 ↩

-

Further details can be found on the Society for Editors and Proofreaders web site: https://www.sfep.org.uk/standards/standards-in-proofreading/ ↩

-

https://atlas.oreilly.com ↩

-

http://shop.oreilly.com/product/0636920028482.do ↩

-

https://www.safaribooksonline.com ↩

-

https://leanpub.com/about ↩

-

Git for Humans, David Demaree, A Book Apart, 2016 ↩

-

First created by John Gruber: https://daringfireball.net/projects/markdown/syntax ↩

-

Pandoc is an open source universal document converter created by John MacFarlane. http://pandoc.org ↩

-

http://prose.io/#about ↩

-

https://www.gitbook.com ↩

-

BookType is open source software. http://sourcefabric.booktype.pro/booktype-22-for-authors-and-publishers/what-is-booktype/ ↩

-

https://editoria.pub ↩

-

https://glose.com ↩

-

http://www.livemargin.com/socialbook/ ↩

-

https://web.hypothes.is ↩

-

http://annotatorjs.org ↩